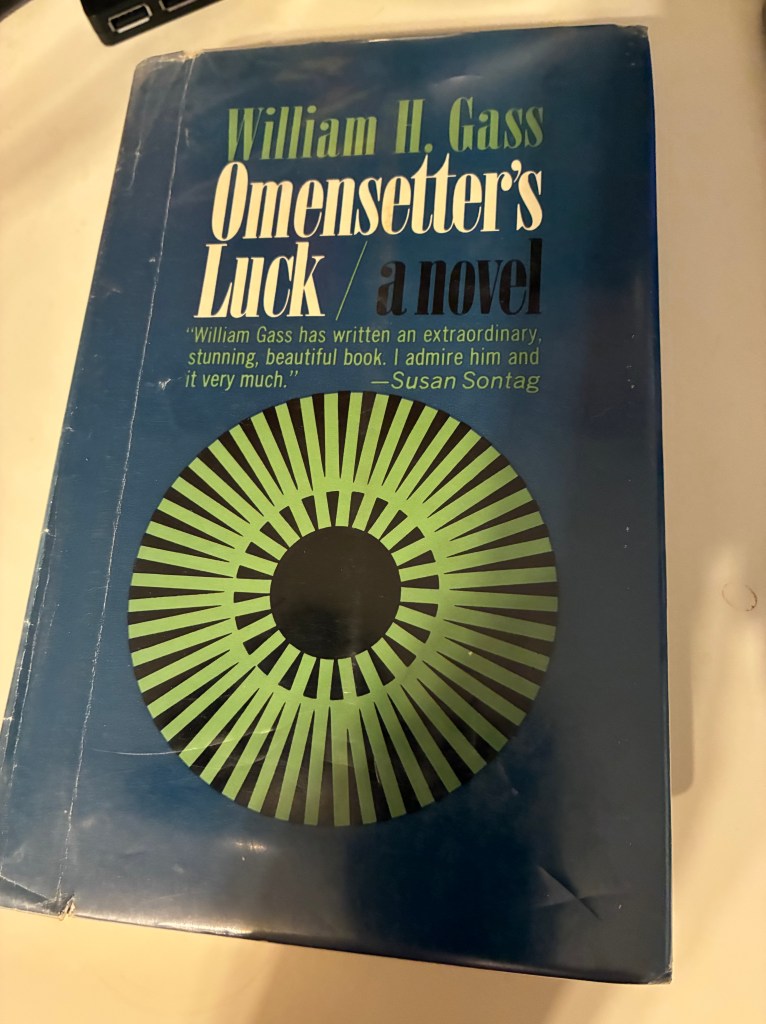

Omensetter’s Luck (1966)

William H. Gass is often regarded as one of the pioneers of American postmodern literature, alongside Thomas Pynchon, Robert Coover, and William Gaddis, among others. Omensetter’s Luck was Gass’s first novel, and the manuscript was stolen from his desk, so he re-wrote the entire thing from memory.

Plot’s not the thing here, and it owes a debt to Faulkner, particularly The Sound and the Fury, in terms of structure and style. There are three sections told from different perspectives, but most of the story finds us lodged in the very unpleasant mind of Reverend Furber. The book is set in a 1890s Ohio town and follows the arrival of the Omensetters. Brackett Omensetter seems to be a primal force, like a large, friendly, and, at first, very lucky bear. His presence disturbs a few locals, especially the Reverend, who, let’s say, has a lot of issues. There’s a murder at the center of the story, but it’s not the focus in the way it would be in a detective novel.

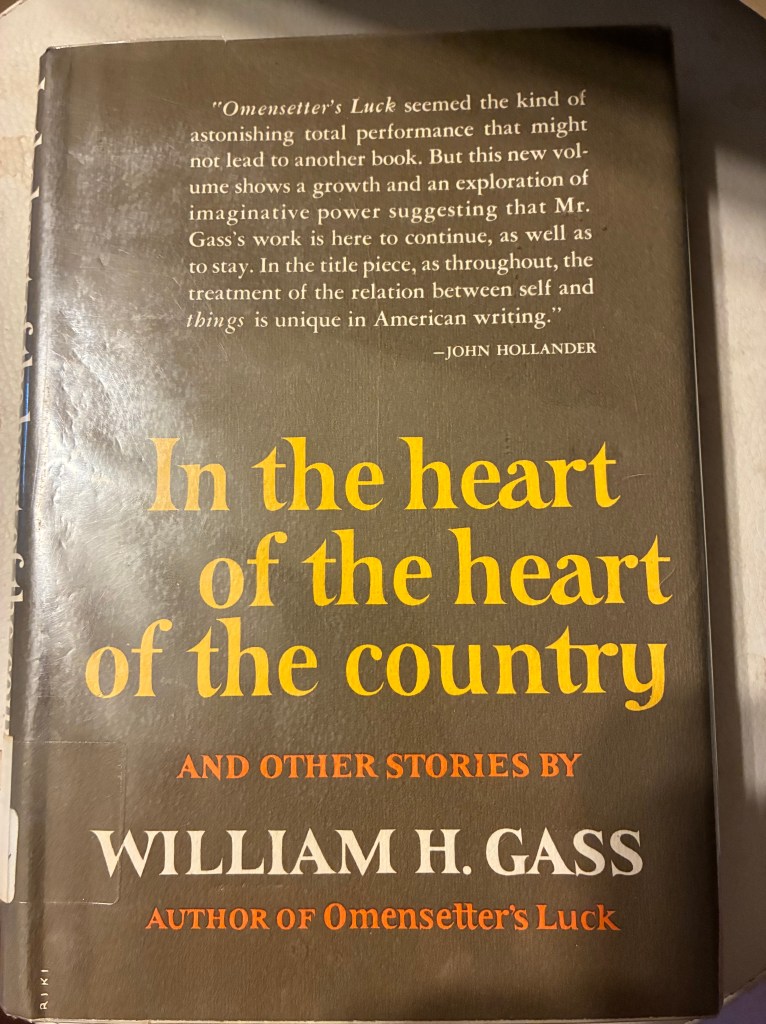

In the Heart of the Heart of the Country (1968)

So far (and I’ll mention the exception), his stories and Omensetter’s Luck are primarily told through the interior lives of characters who are awful, depressed, or spiraling into nihilism, or some mix of these. While the sentences and the art can be beautiful, the characters’ lived experiences are not.

On a first read, I’m questioning how satisfying many of the stories are. Frequently, the narrative’s journey, while certainly not rushing along, is at least interesting; however, many of the stories end in a kind of sputter of insanity that is hard to say is satisfying on a first read.

My favorites were probably “Icicles” and the title story. Probably the best known are “The Pedersen Kid” and “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country.” “The Pedersen Kid” is very good, but I haven’t decided on how much I liked the ending, a similar issue I had with “Icicles.” What I liked about “Icicles” is that the narrator felt like someone contemporary, unlike many of the previous stories set in earlier time periods. The main character is a real estate agent and feels partly like the schlub in Glengarry Glen Ross, but because we get his interior life, he also feels like an early Stephen King character. Many of the stories are narrated by bullies or unpleasant individuals, and I appreciated this bizarre, loserish perspective, paired with poetic prose.

The title story is the exception I mentioned above. Gass is thoroughly postmodern at this point in terms of structure and voice, whereas in the earlier work, it resides more in the voice and cynicism, as well as in the way the plots tend to fizzle into ambiguity. This story is told from the perspective of a person in a small Midwest town, but it also incorporates elements of omniscience. It’s difficult to determine their location. The story doesn’t operate in a traditional way at all. It spirals around various topics, sometimes employing motifs with differing details about the town’s setting and its people. Sections are titled. It sometimes feels like he is riffing on something like a Dickens’ narrative voice or a bitchy version of the Our Town narrator.

Both books contain some exceptional writing, although not as baroque as Faulkner’s. There’s something in the style that leans more toward Cormac McCarthy at his most streamlined and humorous, or Flannery O’Connor, but with a shift to the Midwest, with dabs of the James Joyce of Ulysses.

He has some poetic and musical tendencies that mostly work and, on a sentence level, are sometimes exquisite. His people are often ugly, whether on the surface or within — especially within. There is a humor to it, which may be why he is usually considered postmodern, but it’s difficult to tell how much is humor and how much is a disdain for humanity. He had two wives and five kids, so I guess he wasn’t a total misanthrope.

Despite some complaints, I would reread these and look forward to the reissue of The Tunnel coming next year.